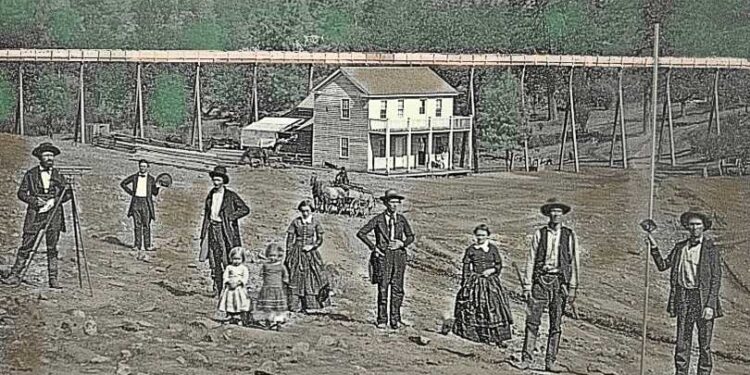

Water, Wood and the Gold Rush: How Flumes and Surveyors Shaped El Dorado County in 1855

In 1855, water was as valuable as gold in El Dorado County, and controlling it required both engineering ingenuity and legal precision. Across the western slope of the Sierra Nevada, miners built miles of wooden water flumes—elevated troughs that carried water from high-elevation streams to dry diggings—while surveyors laid out claims, measured grades and resolved disputes in a rapidly evolving frontier economy.

By the mid-1850s, easily worked placer deposits along rivers and creeks had largely been exhausted. Hydraulic mining, ground sluicing and quartz milling required steady, high-volume water supplies, often far from natural streams. Flumes answered that need. Constructed from locally milled pine or fir, these V- or box-shaped wooden channels were supported on trestles, cribbing or rockwork and engineered to maintain a precise downhill grade over rugged terrain.

“El Dorado County became a laboratory for water engineering during the Gold Rush,” notes the California Department of Parks and Recreation in its historical materials on Sierra Nevada mining. “Flumes, ditches and canals allowed miners to move water across entire watersheds.”

Where Flumes Were Used

Flume systems crisscrossed much of El Dorado County in 1855, particularly in mining districts around Placerville (then known as Hangtown), Coloma, Georgetown, Diamond Springs, Pilot Hill and along the South Fork of the American River. Large water companies—such as the Natoma Water and Mining Co. and the El Dorado Water and Mining Co.—built interconnected networks of ditches and flumes stretching dozens of miles.

In steep canyon areas where digging a ditch was impractical, flumes were suspended hundreds of feet above ravines. Some sections were enclosed to prevent evaporation and freezing, while others were open, allowing debris to spill harmlessly over the sides.

The Role of Surveyors

Surveyors were essential to this system. They calculated grades, staked water rights, mapped claims and ensured flumes maintained the minimal drop needed to keep water moving without eroding the structure. Their work also carried legal weight. California’s emerging doctrine of “prior appropriation”—first in time, first in right—made accurate surveys critical when competing miners and companies fought over water access.

A handwritten notation such as “Mountain House [Norris?] El Dorado Co. Cal 1855” likely refers to a known waypoint or roadhouse used as a reference point by surveyors. Mountain House establishments commonly served as supply stops, lodging and informal landmarks in survey notes, water contracts and mining maps of the period.

Surveyors often worked under harsh conditions, traversing steep slopes and dense forest with chains, compasses and leveling instruments. Their measurements guided not only flume construction but also early roads, town plats and property boundaries that still influence modern El Dorado County.

Why Flumes Mattered

Beyond mining, flumes supported sawmills, powered stamp mills and supplied water to growing towns. They represented one of the region’s first large-scale infrastructure investments and laid the groundwork for later canals, reservoirs and hydroelectric projects.

“The success of many Gold Rush communities depended on their ability to move water,” according to historical interpretations from Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park. “Flumes turned geography into opportunity.”

While most wooden flumes were dismantled or collapsed by the late 19th century, their legacy remains visible in place names, abandoned grades etched into hillsides and early survey records preserved in county and state archives.