By Cris Alarcon, InEDC Writer. (April 30, 2025)

Gilbert C. Cook’s Career in California Law Enforcement

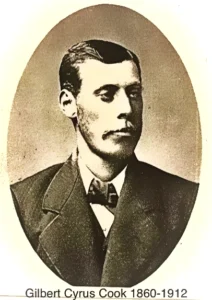

Gilbert Cyrus Cook (1860–1912) was a prominent El Dorado County lawman around the turn of the 20th century. He served as a Deputy Sheriff and even as Deputy City Marshal of Placerville before being elected Sheriff in 1907. Under Sheriff Archie S. Bosquit (1898–1907) Cook helped patrol the Sierra foothills. When Bosquit left office in late 1907, Cook began his own term (Nov. 7, 1907) as El Dorado County Sheriff. His tenure reflected the era’s “frontier justice” – sheriffs and posses acting as the primary law enforcement in rugged terrain.

The 1903 Folsom Prison Escape

Cook’s career intersected with a notorious event in California criminal history: the July 27, 1903 “Bloody Thirteen” escape from Folsom State Prison. Thirteen hardened convicts (serving long and life terms) overpowered guards and took hostages during the break. One guard was killed and others injured before the fugitives fled into the countryside. In the ensuing manhunt, five escapees were eventually recaptured, two died (one by suicide) and six remained at large. Notably, John H. Wood (one of the escape leaders) was caught in Reno in August 1903 and returned to California for trial, and Joseph Murphy (who murdered a guard during the breakout) was later convicted and executed in 1905. This violent prison break – described by contemporaries as “a violent prison break by thirteen inmates” – shocked California and prompted a massive cross-county pursuit (Governor Pardee’s papers noted the “dramatic” escape and its aftermath).

The Foothills Manhunt and Cook’s Role

After the breakout, Cook (then a deputy) joined Sheriff Bosquit’s and other posses in scouring El Dorado’s rough terrain. According to contemporary accounts, the fugitives quickly looted supplies as they fled (including raiding S.D. Diehl’s store at Pilot Hill) and drove off with a stolen wagon of provision. By late afternoon on July 30, 1903, a posse of 42 men (recruited from Placer and Sacramento counties) cornered the group at Pilot Hill. A fierce gunbattle ensued (“seventy or eighty shots” fired), wounding one convict (J.J. Allison) and enabling the hostages to be freed. The remaining convicts scattered into small bands. Company H of the California National Guard (based in Placerville) was mobilized to search the northern foothills. Local farmers reported sightings (e.g. a boy saw five fugitives crossing an orchard at Squaw Creek), and posses fanned out on foot and horseback. Although no primary newspaper source names Cook directly in the chase, family accounts (and the timing) suggest he helped lead or track parties in El Dorado County during this hunt. The convicts even attempted tricks like using cayenne pepper to throw off any hounds. In the end, only six of the escapees were recaptured – and two were hanged – illustrating both the difficulty of the pursuit and the lethal stakes.

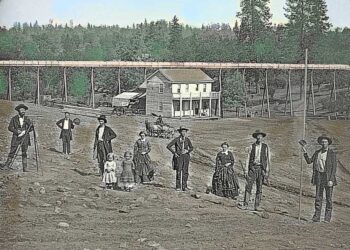

Hi everyone, I’m hoping someone might know something about my family (on my Father’s side) that moved from Indiana to Old Dry Diggins to mine for gold, in 1851. William Newton Cook (1834-1914) was my GGF, his Son Gilbert Cyrus Cook (1860-1912) was a Deputy and then Sheriff of El Dorado County. His Son, my Grandfather, named Gilbert Cook Jr. (1987-1975) was also in law enforcement in the area. His Son and my Father Lawrence Gilbert Cook (1925-1977), was my Biological Father. He worked for a lumber railroad in the ‘40s and later as a Placerville Policeman. I have located a cousin that still lives there, but she had only limited information on my side of the family. I plan to visit Placerville in June, to explore the area and do some research on my own. I live in Albuquerque and have only been close (Interstate 80) to Placerville a few times in the past. I’m looking forward to seeing where my family lived since the 1850s. Photo is from the newspaper story of Sheriff Gilbert C. Cook, and a man with Bloodhounds, on the trail of Folsom Prison escapees, in August 1903. I believe the other photo is of one of the escapees.

Photo of my Father (left side) when he was a Placerville Police Officer in the mid ‘50s.

Steve Todd

He was married to my mother, Marie Cook for a couple of years. Around 1955 -1958. They had a girl named Teresa. She drowned in 1961 in Coloma. She was my half sister, a beautiful little girl. My mom passed away so can’t give you a lot of details.

Gloria Weldy

Wow, thanks for taking the time to share your story with me. My biological mother, Lucille Hess actually lived with my adopted parents during the last three months of her pregnancy. I didn’t discover her until 2008, and was able to meet here before she passed. She wouldn’t tell me anything about my biological father. It was only last year when the 1950 Census was released (I was born in 1949), that I was able to identify L. G. Cook as my father. I was hoping to find a relative or someone that might have family photos of the early family members, starting with William Newton Cook that moved his family to El Dorado Co. In 1851.

Steve Todd

Tracking Hounds and Law Enforcement Dogs

From the 1800s into the early 20th century, lawmen often relied on trained tracking dogs – especially bloodhounds – to hunt fugitives through wilderness. Bloodhounds were prized for their extraordinary scenting ability. As one historian of the breed notes, “Stories of Bloodhounds finding criminals are true… their ability to find people is fascinating”. In California, news accounts report that authorities even brought bloodhounds from Reno (handled by pros like C. E. Terrell of Nevada) to trail the Folsom fugitives. (In fact, the convicts had reportedly stolen pepper from a general store, hoping to confuse the dogs’ scent.) The photo below, from a modern bloodhound trial, illustrates the kind of fieldwork these dogs performed. “Man-trailing” bloodhounds would be run on scent trails in forests and fields, often bringing officers within rifle range of hidden fugitives. In many cases, their use cut down search times dramatically compared to human trackers alone.

Bloodhounds were often accompanied by handlers trained in reading the dogs’ behavior. By training and tradition the breed excelled at trailing one human scent among many. (Legends even tell of bloodhounds tracking fugitives through crowded streets.) The image below shows a typical bloodhound specimen – drooping ears and loose skin – built for scenting on the wind. Law enforcement agencies of the era kept bloodhounds on call for escapes, murders, or missing-person cases. Cook’s posse would have known such dogs by reputation, and might have called on them alongside posses. Local newspapers of the era describe how these dogs “scour” the hills and “scent” fugitives, reflecting their unique role in frontier policing.

Frontier Justice and Policing in Early California

Gilbert Cook’s work must be seen in the context of “frontier” California law enforcement. Even as the 20th century dawned, rural California lacked a large professional police force; sheriffs, marshals, and posses carried out justice. Historian Jo Ann Faragher notes that 19th-century California saw ruthless vigilantism – “vigilantes and various self-appointed arbiters of informal justice” carried out lynchings and hangings in the early Gold Rush era. By 1903 this had formalized into elected sheriffs and soldiers (Company H of the National Guard) enforcing order, but the ethos was still close to the Old West. Cook and his contemporaries would patrol unpaved roads on horseback, answer telegraphed alerts from neighboring counties, and work with ad-hoc posses of citizens. In this era, a successful officer might personally participate in a shootout or lead bloodhounds into the brush. The Folsom pursuit was in many ways a classic frontier manhunt – multi-county cooperation, dramatic gunfire, and even technology like telephones and telegrams to coordinate searches.

Cook’s later election as El Dorado County Sheriff (1907–1912) came at the end of this “wild” era. He arrived in office just as California was beginning to modernize its police work (radio would come a few decades later). Throughout, however, his service exemplified the transitional generation that bridged vigilante justice and the emerging modern police state. Newspaper coverage of the time – from the San Francisco Call to regional papers – praised officers like Cook for “daring” and “horseback endurance” in pursuing outlaws. In sum, Gilbert C. Cook’s law enforcement career (from deputy to sheriff) and his role in the post-1903 escape manhunt illustrate the rugged, hands-on policing of early California. The combination of armed posses and tracking hounds in that chase was emblematic of a frontier justice system on the move into the 20th century.

Sources: Contemporary reports and histories document these events. For example, G. J. Carpenter’s Pioneers of El Dorado (published circa 1906) describes the July 1903 showdown at Pilot Hill, noting the posse’s shootout and the stolen supplies found in the fugitives’ camp. Period newspapers (e.g. San Francisco Call, Sacramento Bee, Placerville Mountain Democrat) covered the Folsom escape and manhunt in detail. Modern analyses of Bloodhound history confirm the breed’s use by police in this era. Together these sources give a fuller picture of Cook’s era of frontier law enforcement.