PLACERVILLE, Calif. —

Long before Highway 50 etched its way into the granite backbone of the Sierra Nevada, freight teams clattered east from Sacramento, climbing into the hills of El Dorado County. Their destination: the Comstock Lode of Nevada—home to one of the richest silver strikes in American history. Their path: the Placerville Route, known in the 1860s as Johnson’s Cutoff.

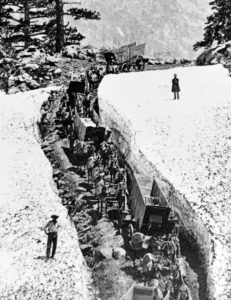

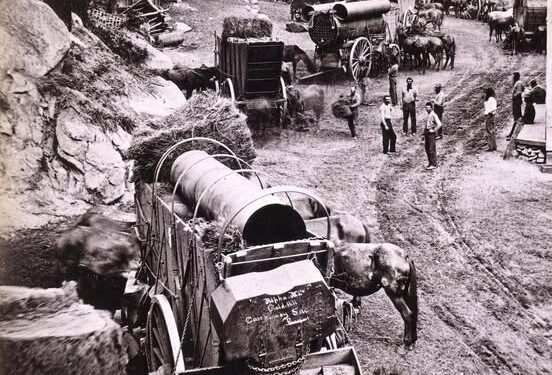

More than a road, the route became a lifeline. After silver was discovered near Virginia City in 1859, the Comstock’s demand for lumber, tools, flour, beef, and booze skyrocketed. By 1860, the Placerville Route was bustling with freight wagons pulled by up to 16 mules or oxen, each load weighing several tons. From early spring through late fall, the teams moved daily, feeding the mines with everything from blasting powder to coffee beans.

The Johnson Cutoff, first scouted by John Calhoun Johnson in 1852, became the shortest and most direct year-round route over the Sierra. Starting in Sacramento, it climbed through Placerville, then wound over Echo Summit before descending to Lake Tahoe and across Nevada’s desert to Virginia City. With the Pony Express also using this path between 1860 and 1861, Johnson’s route became the West’s most vital corridor.

Freighting was brutal work. Dust and axle-deep mud alternated with granite switchbacks and treacherous descents.

“It took strong men and stronger animals,”

said historian Alan Hodge of the El Dorado County Historical Museum.

“Freighters often walked beside their teams for days on end—eating trail food, sleeping under their wagons, and braving robbers and storms.”

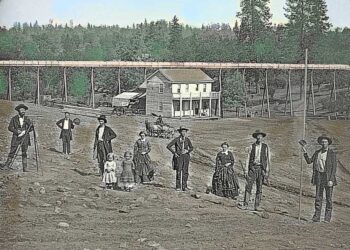

Stops along the route became local legends. Strawberry Valley House, Sportsman’s Hall, and Fresh Pond were more than inns—they were essential rest stations where animals could be watered and fed, wagons repaired, and drivers could catch a hot meal. Oxen needed up to 30 pounds of forage per day, while drivers relied on flapjacks, bacon, and gallons of hot coffee.

According to period accounts, by 1862 the volume of freight over the Johnson Cutoff was staggering. Some weeks saw more than 500 wagons cresting the Sierra. The flood of goods not only fueled Nevada’s mining towns, but transformed El Dorado County into a logistics hub. Blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and stables lined Main Street in Placerville. Ranchers along the route sold hay and meat directly to the teamsters. Even local children earned coins carrying water to thirsty travelers.

While the completion of the Central Pacific Railroad in 1869 shifted much of the heavy freight eastward via Donner Pass, the Placerville Route’s legacy endures. Modern Highway 50 follows much of the original path, and today’s travelers often pass historic markers unaware that beneath their wheels lies the ghost trail of mule teams and grit.

“Without that road and the men who drove it,”

said Hodge,

“the Comstock might never have boomed—and Placerville might have faded away.”