Logging in El Dorado County: From Gold Rush Roots to Timber Titans

By Cris Alarcon | El Dorado County Press | July 8, 2025

PLACERVILLE, Calif. — Before the apple orchards of Camino or the cabins of Jenkinson Lake, the lifeblood of El Dorado County flowed from its forests. From the mid-1800s through the early 20th century, timber—not just gold—was the resource that built the West.

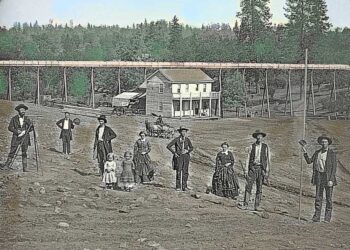

By 1850, the Gold Rush had drawn more than 20,000 settlers to the region, upending a Native population that had managed the land with fire and balance. The newcomers needed shelter, fuel, and infrastructure—and fast. Axes rang through virgin groves as lumber became the unsung foundation of a booming mining economy.

“People often forget that every flume, mineshaft, and false-fronted saloon in Hangtown started with a felled tree,” said Anthony M. Belli, a local historian and author of Sawdust and Gold Dust: El Dorado’s Timber Years.

From Axes to Industry

Early operations were brutal. Trees up to 10 feet in diameter were brought down by hand using crosscut saws. Logs were dragged to crude mills by oxen or horses, often processed in water-powered sawmills built along creeks like Weber and Camp Creek.

By the 1860s, steam power replaced water, and mills scaled up. Entire towns like Grizzly Flat, Omo Ranch, and Kyburz emerged around logging operations. Chinese laborers, many of whom were originally brought in for rail construction, also played key roles in flume-building and forest clearing, though their contributions remain underrecognized.

Michigan-California and the Cable That Changed Everything

In 1866, New England immigrant Horatio Livermore tried to float logs down the American River to Folsom. Nature had other ideas. Several drives failed, with millions of board feet stranded or lost in floods. A dam was built near Salmon Falls, but it wasn’t enough.

By 1901, the El Dorado Lumber Company—successor to Livermore’s venture—engineered a breathtaking solution: a 2,650-foot cable crossing over the American River, suspended 1,200 feet above the canyon floor. Logs from the Pino Grande mill were sent on railcars over this cable to the planing mill in Camino.

“Imagine a flatcar full of lumber swinging like a pendulum across a mile-wide canyon—that was the daily commute for timber in the Sierra,” said Belli. “And it worked.”

This feat of engineering turned the tide. By 1905, the mill was producing 35 million board feet annually. A narrow-gauge railway and 21 trestles connected remote logging camps to Camino, and from there, a standard-gauge train carried finished wood to Placerville and Sacramento.

Booms, Busts, and Rebirth

The 1907 financial panic crushed El Dorado Lumber’s banking backers. Camino’s population dropped from 500 to just six. The forests stood silent until Michigan lumberman C.D. Danaher bought the assets in 1911, restarting operations—but economic troubles and poor timber selection doomed the effort.

His brother James Danaher and nephew Ray took over, continuing work as the R.E. Danaher Lumber Company. Despite fierce setbacks, these early lumbermen left behind a complete “woods-to-railhead” system—one of the most advanced in the Sierra.

Logging’s Legacy

The environmental toll of early logging was severe. Clear-cutting led to erosion, wildfire risk, and habitat loss. The U.S. Forest Service, established in 1905, began regulating timber harvests by 1910, leading to more sustainable (and bureaucratic) forestry practices.

Today, logging is no longer a dominant industry, but its legacy is visible. The Camino & Placerville Railroad still operates on Sundays, offering rides through once-busy timber corridors. Apple Hill’s orchards now sit atop logged lands. And the El Dorado County Historical Museum in Placerville preserves this rugged heritage through photos, oral histories, and restored rail cars.

“Logging gave us more than buildings—it gave us connection, commerce, and identity,”

said Belli.

“We owe the backbone of this county to the men who carved it out, tree by tree.”

The early history of lumber in El Dorado County, California, is deeply interwoven with the Gold Rush, the settlement of the Sierra Nevada foothills, and the explosive growth of mining towns like Placerville, Georgetown, and Grizzly Flat. The timber industry not only supported gold mining but also shaped transportation, land ownership, and even community identity. Here’s a comprehensive breakdown:

🌲 I. Origins: Pre-Gold Rush and Native Use

-

Indigenous stewardship: Before settlers arrived, the Nisenan and Washoe peoples used local trees—especially cedar and pine—for shelter, basketry, and fuel. They practiced seasonal burning to manage underbrush and promote acorn production, which kept forests relatively open.

-

Mexican land grants (pre-1848): Under Mexican rule, large tracts of what would become El Dorado County were granted to rancheros. Though not focused on timber, this era marked the beginning of formal land ownership which would later impact lumber claims.

🪓 II. The Gold Rush Boom (1848–1860s): Timber as Mining Infrastructure

-

1848: Discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma triggered a massive influx of miners.

-

Lumber demand skyrocketed: Wood was essential for:

-

Flumes and sluices for placer mining.

-

Mine shafts and tunnel supports.

-

Buildings: saloons, hotels, homes, and false-fronted storefronts.

-

Fuel: firewood for heating and cooking.

-

-

Sawmills proliferated: Many were water-powered, situated along creeks like Weber Creek, Camp Creek, and the South Fork of the American River.

-

One of the first mills was built by James W. Marshall (of gold discovery fame), near Coloma.

-

-

Logging was local and brutal: Trees were felled by hand with axes and crosscut saws. Logs were skidded to mills using oxen or horses.

-

Placerville (then known as Hangtown) became a central lumber depot, as it sat at the crossroads of several mining routes.

🚂 III. 1860s–1890s: Industrialization & Railroad Logging

-

Logging towns formed:

-

Grizzly Flat, Omo Ranch, and Kyburz emerged as logging outposts.

-

Some of these towns were originally mining camps that transitioned to timber.

-

-

Steam-powered sawmills began to replace water-powered ones in the 1860s.

-

Railroads extended logging reach:

-

Michigan-California Lumber Company (formed in the late 1800s) became one of the region’s most dominant players.

-

It built narrow-gauge logging railroads to haul timber out of remote canyons.

-

The company’s incline railways—particularly in Camino and Pino Grande—became feats of engineering that allowed logs to descend thousands of feet.

-

-

Chinese laborers played an unheralded role, cutting timber and building flumes.

-

Box factories sprang up in Placerville and Camino, producing crates for fruit, wine, and mining equipment.

🏔️ IV. Early 20th Century: Consolidation & Forest Management

-

By the early 1900s, major players like American River Land and Lumber Company and Michigan-California Lumber Company consolidated lands and operations.

-

US Forest Service began regulating logging on national forest lands.

-

El Dorado National Forest was established in 1910, making sustainable practices more common (at least in theory).

-

-

The El Dorado Western Railway and Placerville Lumber Company served dual purposes—moving timber and passengers. They linked mill towns with Placerville and Sacramento.

🔥 V. Environmental Impacts and Fire Risk

-

Clear-cutting and lack of reforestation practices led to soil erosion, stream silting, and wildfire risk.

-

Slash piles and debris from mills and railways were often left unburned, contributing to intense wildfires.

-

The overharvesting of old-growth pine and fir would later prompt reforestation campaigns.

⚙️ VI. Legacy and Preservation Today

-

Camino’s Apple Hill region grew on the cleared timberland once held by Michigan-California Lumber.

-

The El Dorado County Historical Museum in Placerville houses artifacts from the region’s timber past, including rail cars, mill equipment, and photos.

-

The El Dorado Western Railroad operates a restored segment of logging railway on Sundays, preserving the memory of timber transport.

-

Sly Park (Jenkinson Lake) was once the site of active logging; today it is a popular recreation area.

📚 Notable Historical Figures

-

James W. Marshall: Built early sawmills after discovering gold.

-

Harvey Gross: Owned timberlands; helped develop tourism and lumber simultaneously.

-

Michigan-California Lumber Co. engineers: Built the legendary cable incline at Pino Grande.

🧾 Primary Sources and Historical Reading

-

“The Michigan-California Lumber Company: Logging and Railroads in the Sierra Nevada” – excellent historical overview with photos.

-

El Dorado County Historical Society archives – includes maps, oral histories, and mill registries.

-

U.S. Forest Service timber harvest records from 1900–1945.

📍 Summary

The lumber industry in El Dorado County rose as a vital companion to the Gold Rush, providing essential infrastructure and fueling economic growth. It transitioned from hand-hewn, water-powered operations to a mechanized system with railroads, mills, and national corporate players. Though it left scars on the land, its legacy remains in the communities it built, the trails it carved, and the lessons it taught about balancing industry with stewardship.

Logging Days 2025 Returns to Pollock Pines: Celebrate El Dorado’s Timber Legacy

Logging Days 2025 Returns to Pollock Pines: Celebrate El Dorado’s Timber Legacy