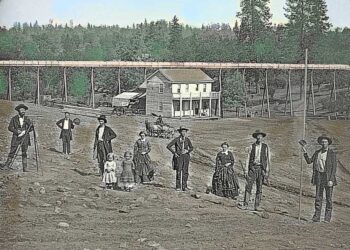

PLACERVILLE, Calif. — Morning light catches the weathered brick facades along Main Street as shops unlock near the Fountain & Tallman Museum. Wooden signs creak softly in the foothill breeze, much as they would have in the years after gold was discovered nearby. More than 170 years later, Placerville’s Victorian-era storefronts remain active businesses, preserving Gold Rush architecture not as exhibits, but as part of everyday life in El Dorado County.

Founded in 1848 following the discovery of gold at Coloma, Placerville—originally known as Hangtown—quickly became a supply and transportation hub for miners heading into the Sierra Nevada. Today, the city of about 10,000 residents sits at roughly 1,900 feet elevation along U.S. Highway 50, about 45 minutes east of Sacramento, where its commercial core still reflects mid-19th-century construction.

The Fountain & Tallman Museum occupies the oldest surviving building on Main Street, a rock-rubble structure completed in 1852. The surrounding downtown area is listed as California Historical Landmark No. 475, recognizing Placerville’s importance in mining, freight hauling and early transportation routes linking the Central Valley to the high Sierra.

“These buildings weren’t saved by accident,” said a representative of the El Dorado County Historical Society. “They survived because the community chose durability, and later chose preservation.”

Fire, rebuilding and the Bell Tower

Fire, not gold, proved to be the town’s greatest early threat. During the 1850s, repeated fires swept through Hangtown, fueled by wooden buildings, open hearths and densely packed businesses. The most destructive blaze, in 1856, destroyed much of the downtown, forcing residents to rebuild with brick and stone—materials that still define Main Street today.

In response, the community invested in fire detection and warning systems. The Bell Tower was constructed in 1860 to house a fire bell that could be heard throughout the narrow canyon. When rung, it signaled merchants and residents to respond before flames spread block to block.

“The bell symbolized survival,” local historians note in museum exhibits. “It marked the moment Placerville began building not just for commerce, but for endurance.”

The Bell Tower remains a defining downtown landmark, its chimes continuing to mark the hours, long after volunteer bucket brigades gave way to modern fire protection.

Victorian architecture in working order

Placerville’s historic storefronts function as active businesses rather than preserved shells. Cafes, antique shops and galleries occupy the same buildings that once housed saloons, mercantiles and freight offices. Original ironwork, wooden window frames, stone lintels and corbelled brickwork remain visible, especially during winter when bare trees reveal architectural details hidden in summer.

Unlike nearby Nevada City, which emphasizes arts and festival culture, Placerville’s preservation centers on mining and transportation history. The town’s Main Street follows a linear commercial pattern shaped by wagon traffic and stagecoach routes rather than hillside residential development.

Gold Bug Mine’s tangible history

One mile north of downtown, Gold Bug Park offers visitors a direct connection to hard-rock mining. The Gold Bug Mine features self-guided audio tours extending 352 feet underground, where timber shoring, tool marks and exposed quartz veins remain intact. The mine maintains a constant temperature of about 55 degrees year-round, a stark contrast to winter foothill days that typically range from the mid-40s to mid-50s.

An unhurried downtown rhythm

Early mornings on Main Street reveal Placerville at its most authentic. Sidewalks remain quiet as cafes open gradually and locals settle into window seats with newspapers and coffee. The commercial core spans just five blocks, walkable in minutes, but historical plaques, benches and storefront details encourage visitors to slow down.

There are few modern intrusions. No parking meters regulate browsing. Tour buses are uncommon on weekdays. Museums are staffed by volunteers rather than costumed interpreters, reinforcing the sense that Placerville is lived in, not staged.

Beyond gold: Apple Hill and adaptation

Ten miles east, the Apple Hill farming region reflects the area’s transition from mining to agriculture. December brings quiet farm stands and dormant orchards, a sharp contrast to the heavy crowds of fall harvest season. Together, Apple Hill and Main Street illustrate how Placerville adapted after the Gold Rush while keeping its architectural core intact.

Local tourism officials say travelers increasingly seek destinations that offer genuine history rather than themed recreations. Placerville’s identity remains tied to Highway 50, mining infrastructure and small-town continuity.

As late afternoon sun warms the stone walls of the Fountain & Tallman Museum, Main Street gradually empties. A few locals linger at sidewalk tables as the Bell Tower marks another hour. In Placerville, Gold Rush history lives on—not behind glass, but in buildings still doing what they were built to do.